Vacant (and confused): How to tell San Francisco’s two vacant storefront measures apart

Oct 27, 2022

This article was originally published in San Francisco Business Times.

When San Francisco voters approved Proposition D, also known as the vacant storefront tax, in early 2020, retail broker Hans Hansson and others in local real estate were incensed at the thought of a penalty designed to address a problem that in their minds didn’t exist.

What landlord would decide, as the punitively minded measure envisions, to leave their space vacant, forgoing months of paying occupancy, to nab a slightly higher-paying tenant?

Now, as Hansson and their client landlords and retail storefront operators approach the first filing deadline for the tax at the end of February 2023, the dominant feeling is confusion.

“Some retail owners started coming to us and asking, ‘what’s this all about?’” Hansson told me. “I kind of lost sight of it because, frankly, with Covid it was delayed and became a kind of moot point. Yet now they’re going to improvise it.”

(Hans Hansson, president of Starboard CRE, at a vacant commercial space on Powell Street in Union Square. Adam Pardee)

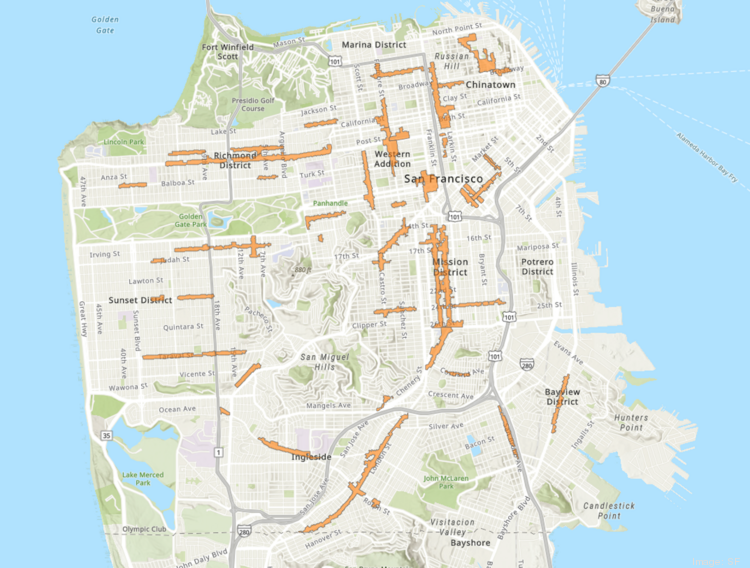

It turns out the way the city of San Francisco defines vacancy depends on which office you ask. The city’s Department of Building Inspection, or DBI, classifies a property as a “vacant or abandoned” if the ground-floor street-facing space is unoccupied for more than 30 days. Its data shows there are at least 500 vacant retail storefronts across the city. See the map below with dots showing the concentration.

Many of these properties, if located in commercial or transit corridors, will become subject to the city’s commercial vacancy tax, which penalizes landlords of storefronts vacant for at least six months out of the year. It took effect at the start of this year after a one-year pandemic delay; property owners must file their first reports with the city by the end of February 2023.

A major source of confusion is that what’s considered vacant —and penalizable — differs between the DBI and the city’s Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector.

Here we unpack two of these mechanisms: the DBI’s vacant or abandoned building registry — a 2009 ordinance whose requirements were significantly strengthened in 2019 — and the new commercial vacancy tax, administered by the Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector.

San Francisco’s vacant and abandoned buildings

No matter where your storefront is situated in the city, the DBI — responsible for enforcing building codes — requires the property owner of a tenant-less storefront to pay $711 to register it as a “vacant or abandoned building” within 30 days.

Changes to the law made by the Board of Supervisors in spring 2019 added extra teeth to the requirements, ostensibly to make landlords move more urgently. The fee must be paid up front; no more exceptions for a storefront being advertised for lease; and property owners are subject to a penalty four times the fee ($2,844) if the storefront isn’t registered within 30 days. The $711 fee is partially refunded if the storefront locks in a tenant within 12 months.

On top of that, owners also need to file an annual safety report from a “licensed professional” who can assure the store’s interior and exterior is up to code. The idea is, no one wants an empty storefront to host squatters or become a fire hazard (or both) because of dangerous materials or unsecured entrances like, say, a broken window. That report is due when the owner pays the registration.

Technically, the 30-day window for landlords doesn’t start until the DBI actually notices a vacancy. Unlike traffic cops, the DBI isn’t driving around scoping out potential violators. Instead, the city relies on the community to file a complaint to sound the alarm on potential blight.

Call it another reason to be nice to neighbors, or a chance to be opportunistic if you’re a prospective tenant. Because of this enforcement dynamic, it is in property owners’ best interest to avoid reporting a vacancy until the DBI has formally issued them a notice of violation, as it would mean shrinking one’s own window to find the best tenant (and lock in preferred rates) to the mere 30 days.

On the flip side, a potential tenant could consider it due diligence to anonymously report any retail listing they see, to put more pressure on a landlord to offer favorable terms. For the property owner, however, a worst-case $2,844 fee could be well worth it if it means securing a better tenant for years to come.

Typically DBI investigates complaints within a few business days, deploying an inspector to the field. The inspector surveys the site and notifies the owner of the complaint — and if found to be vacant, posts a notice of violation (NOV) on the premises.

If the building owner doesn’t respond to the inspector’s follow up contact attempts by phone, email and mail, the next step is a directors’ hearing in which the property owner can plead their case before a five-person body of DBI officials. That body votes by simple majority whether to delay or drop the fee or request the city attorney’s office to take out a lien on the property.

In some cases that lien prevents the owner from selling the property until the vacancy — its registration with the city, not the supplying of a tenant — is addressed.

San Francisco’s commercial vacancy tax

Another arm of the city, the Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector, wields the other bureaucratic deterrent against empty storefronts, this time by penalizing landlords with extended vacant spaces in commercial and transit corridors who, the thinking goes, are inclined currently to keep space empty in the hopes of higher-paying tenants.

The corridors where the tax applies are shown in the map below. Notably, it does not include the Financial District and Union Square.

Commercial retail brokers and landlords dispute how common this is. Landlords — like everyone else — are beholden to what the market will bear and say that the incentive to have a rent-paying tenant at all outweighs any possible rate gains from holding out for a higher-paying one. Still, the argument against the idea of deadbeat landlords stuck with San Francisco voters, who approved the ordinance known as Prop. D in early March 2020.

The tax’s initial effective date of January 2021 was later delayed to January 2022 — providing some extra breathing room amid the pandemic fallout — and owners will have to start filing a report with the city about the status of their spaces for 2022 in February 2023.

Every owner and storefront occupant in the applicable commercial districts is required to file a special “commercial vacancy tax return” for the preceding year by the last day of February.

A commercial space is “vacant” if it is unoccupied, uninhabited or unused for more than 182 days — consecutive or not — in a calendar year. The penalty amounts to about $250 per linear foot of street-facing storefront of ground-floor vacant space located in named neighborhood commercial or transit commercial districts as they existed in March 2020. The tax escalates to $500 per linear foot for a second consecutive year of vacancy, and $1,000 per linear foot in the third year onward. The tax is due at the time the return is filed.

A Treasurer and Tax Collector spokesperson said the procedure is no different from the information required in filing other commercial taxes and for the “vast majority” of businesses “it’ll be very quick.” The office has been doing outreach with landlords and businesses in the areas subject to the tax to bring them up to speed with the requirements.

Whoever is responsible for the property being vacant is the one who must pay the tax — the owner who hasn’t leased or occupied it, the lessee if the space isn’t subleased or the sublessee if it hasn’t occupied it.

Enforcement will be to some extent a learning process for the city: The Treasurer is waiving the penalty for forgetting to file a commercial vacancy tax return for the tax years of 2022 and 2023 as filers adjust to the requirements. Property owners will still eventually owe what tax they are supposed to pay for those years but won’t be dinged for filing late.

There are some notable exemptions to paying (but not filing for) the tax. Nonprofits are exempt. And a lessee who operated a space for more than 182 days consecutively during a lease of at least two years won’t be liable for the tax for the rest of the lease, whether or not the space is vacant.

Take, for instance, a restaurant operating for the first eight months of a five-year lease but then shuttering before the end of its first year. The landlord would have until the end of those five years before it is again subject to the vacancy tax, and the restaurant wouldn’t have to pay.

The Controller’s Office estimated prior to the Prop. D vote the tax would net up to $5 million in revenue annually, with higher revenue expected during times of economic downturn.

The city’s retail landscape has changed dramatically since that projection was made, with neighborhood retail corridors ultimately rebounding to greater strength than ever while downtown and tourism-reliant areas hollowed out.

The Controller says it isn’t working on a revised projection of the tax proceeds. The earliest that would be possible, the office told me, would be following the first year of returns in 2023. Besides, they added, the tax isn’t designed as a large revenue generator anyway — rather, it’s a means to incentivize landlord behavior.

In September, the Board of Supervisors passed legislation enabling the Treasurer’s Office to make information about those tax returns publicly available, similar to what is done with the portal for business registrations. The info made public will include the name of the person or entity required to file the tax at each address, and whether they filed; name of the person required to pay the tax — if their space stays vacant too long — and the tax rate applicable to that commercial space for that tax year.

As far as vacancy is counted, not every day of an empty storefront is treated equally. While an owner is waiting on a building permit, the vacancy clock freezes for up to one year. The clock stops another year for construction, starting after the first permit is issued. The vacancy clock freezes, too, for 183 days after a full conditional use permit application is filed (for instance, asking for an exception to a neighborhood’s ban on formula retail).

Acknowledging the notoriously glacial pace for processing applications, the freeze extends to the end of the year if it has been more than 183 days without a ruling from the Planning Commission. It also stops for the two-year period following the date of severe damage to the property that makes it unusable, such as a fire or natural disaster.

THE LAWS AT A GLANCE

Abandoned or Vacant Buildings

- 2009 ordinance amended by the Board of Supervisors in 2019.

- Applies to buildings anywhere in the city.

- Requires owner to register as a “vacant or abandoned building” within 30 days of becoming vacant and pay $711. The fee is partially refunded if the storefront locks in a tenant within 12 months.

- Owner must file an annual safety report from a “licensed professional” who can assure the store’s interior and exterior is up to code upon registration.

- If owner does not register in 30 days, city levies a penalty of four times the registration fee, or $2,844.

- Enforcement is a complaint-based system.

Commercial Vacancy Tax

- Voters approved Prop. D in March 2020.

- Applies only to certain retail corridors and neighborhoods.

- Commercial space is considered “vacant” if it is unoccupied, uninhabited or unused for more than 182 days — consecutive or not — in a calendar year. There are enforcement delays while seeking permits.

- Owners of vacant storefronts will pay $250 per linear foot of street-facing storefront of ground-floor vacant space. The tax escalates to $500 per linear foot for a second consecutive year of vacancy, and $1,000 per linear foot in the third year onward.

- Exemptions include nonprofits and businesses who lease space for at least 182 days consecutively during a lease of at least two years.

- Enforcement: Normal taxation enforcement applies.